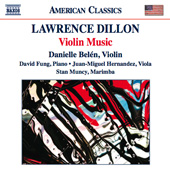

A new release on Naxos Records (Catalogue no. 8.559644)

“an hour of music that is often profound without being pretentious, sometimes light-hearted but never ‘lite’, humorous without being arch, and immensely appealing but never frivolous. According to Naxos’s usual formula, {American composer} always = {American Classics}, but sometimes there is more than a touch of prescience about such fundamentally commercial choices.” — MusicWeb International

- Mister Blister

Danielle Belén, violin - Facade

Danielle Belén, violin

David Fung, piano - Bacchus Chaconne

Danielle Belén, violin

Miguel Hernandez, viola - Sonata: Motion

Danielle Belén, violin

David Fung, piano - Spring passing

Danielle Belén, violin

Stan Muncy, marimba - Fifteen minutes

Danielle Belén, violin - The Voice

Danielle Belén, violin

David Fung, piano

Danielle Belén, 2008 Grand Prize Winner of the Sphinx Competition, makes her debut recording on this disc of violin works by Lawrence Dillon.

In the 25 years that separated 1983 from 2008, the music world underwent dramatic shifts in technology, resources and fashions. Through it all, Lawrence Dillon’s artistic concerns remained steadfast. A love for lyricism, a dash of wit, and what he has called “an irresistible urge” to connect with the Classical music heritage have remained easily identifiable hallmarks of Dillon’s music. The nine works on this recording trace these ongoing characteristics, which can also be found in his vocal, chamber and symphonic works, through the lens of music featuring the violin.

Mister Blister and Fifteen Minutes

In the summer of 2006, violinist Piotr Szewczyk organized a project he called Violin Futura: he asked fifteen composers to each write one short piece—two to three minutes—for unaccompanied violin. Dillon agreed to do it, thinking a short solo piece would be an easy task. Months went by, though, and “I became confused about the requested duration,” Dillon writes, “thinking Piotr had asked for a one-minute piece, at which point I found the project causing me more trouble than I had imagined.” The problem wasn’t how to write a short piece, but choosing which of an infinite number of short pieces he should write.

“After procrastinating until a couple of weeks before the deadline, I finally gave up on choosing which piece to write, and wrote sixteen of them,” Dillon writes. “I sent them all to Piotr, leaving him to decide which one to play.”

Szewczyk wrote back, politely correcting Dillon’s mistake, explaining that he was supposed to have written a piece between two and three minutes long, as opposed to the one-minute compositions that had been provided. To make amends for his error, Dillon dashed off Mister Blister, a speedy showcase for virtuosic violinist, that afternoon.

“I was raised not to waste anything,” Dillon writes, so he collected and rearranged the other sixteen pieces into a whimsical meditation on celebrity called Fifteen Minutes, after Andy Warhol’s observation that “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for fifteen minutes.” Fifteen Minutes requires the violinist to shift styles drastically from one moment to the next (sometimes several shifts within the course of a single movement), surmount enormous technical challenges, and even play kazoo (in Dissonance). The set concludes with a take-off on the most famous minute-long piece in history, Chopin’s Minute Waltz, from which Dillon removed one beat from each measure to create Minute March—rounding off this quirky set with a bit of postmodern decomposition.

Ultimately, the combination of Dillon’s comical mistake and his frugality paid off: Szewczyk gave the premières of both Mister Blister and Fifteen Minutes and posted them on his website, where Danielle Belén found them a year later, when she was trying to decide which American composer to record on her début album.

The movements of Fifteen Minutes are titled:

Grand Entrance

Distractions

Runaway

Jump Back

Sway

Memory

Contained

Foolery

Round

Gripped

Clubbed

Dissonance

Self-Absorption

Carried Away

Listening

Minute March

Façade

In the early 1980s it was fashionable for composers to write thorny, modernist works with glimpses of traditional tonality peeking through. “I thought it would be much more interesting, and more in keeping with my life experiences, to create a piece that punctured a sweet surface with a passage of intense fragmentation and distortion,” writes Dillon. Façade takes an 1890ish waltz, a pretty salon melody, and twists it through some increasingly irrational harmonic shifts until it shatters into inarticulate fragments. After a minute or two of stumbling about in confusion, it gradually reassembles itself into a fragile version of its former self.

The only work on this disk from his student days, Façade made quite a stir at its première. Dillon’s colleagues were angry, sarcastic, contemptuous. One distinguished professor went so far as to tell his students that they should never perform Dillon’s music. Fortunately, that advice has gone largely unheeded: Façade has had as many performances as any other work Dillon has written. It has found a particularly passionate proponent in Danielle Belén, who immediately took to the piece upon first hearing. Façade, she says, “reflects the image I’d like to have of myself…warm, but with a touch of quirk and edginess…I’d always kind of craved a piece like it.”

Bacchus Chaconne

In 1989, Dillon received a commission for a concerto from a well-known cellist. He spent a year and a half working on it, amassing hundreds of pages of drafts taped to the walls and ceiling of his studio. “I had decided, in my youthful enthusiasm, that this cello concerto would be my magnum opus,” Dillon now chuckles. “I tried to include everything I knew and felt about music.”

Just as he was completing the final draft, a phone call informed him that the commission had been cancelled.

The shock of suddenly being left with an enormous, nearly completed score and no hope of a performance was devastating. After a few months of despondency, Dillon decided that he would have to destroy the concerto in order to move on. “I presided over a ritual burning of the manuscript and drafts,” he recalls, after which he wrote a piece that would be its polar opposite: Bacchus Chaconne.

Bacchus Chaconne starts with a slow, elegiac canon, but then abruptly shifts gears into an irreverent, back-beat-dominated dance. The violin and viola engage in a bit of call-and-response competitiveness, each trying to out-do the other in embellishing a simple, repetitive chord progression, the chaconne of the title. In the end, this cheeky little piece helped clear the air for the composer, and he was able to resume work with a fresh vigor.

Sonata: Motion

Though it was originally scored for flute and piano, Dillon had always had in mind that Sonata: Motion could be adapted for violin. When Danielle Belén contacted him in the fall of 2008 about recording his complete violin works, he decided the time for an adaptation had come.

The first movement (Motion/Emotion) is a perpetual motion featuring a persistent two-against-three against-four rhythm. The second movement (Emotion/Commotion) is like a kid sister to Façade: a violent opening gives way to an introspective passage that gradually drifts off into a slightly tainted B flat major.

The final movement (Commotion/Motion) is in rondo form, with a folk-like melody framed by wildly antic homages to early rock-and-roll.

Spring Passing and The Voice

Starting in the early 1990s, Dillon began writing a number of vocal works to his own texts. Several of these songs have been subsequently transcribed for instruments. Spring Passing for violin and marimba and The Voice for violin and piano are two examples.

Spring Passing is an elegy for Dillon’s father, who died of a brain tumor when the composer was two years old. He writes, “I don’t remember him, but he died during locust season, which recurs every seventeen years in New Jersey, where I grew up. 34 years later, an infestation brought the event freshly back to my mother’s mind.” When she described it to him, he responded by writing a brief song:

When your fingers came undone,

I could hardly hold them by,

I closed my eyes and saw them gone,

Gray blossoms in the road again,

Gray petals in the sky.

When your hands released the line,

I could hardly watch them fly,

And though I tried, I knew they’d won.

Gray blossoms in the road again,

Gray petals in the sky.

When your arms arose alone,

I could hardly hold my ground,

Yet here I am, the years gone by,

Now every hand I see is mine,

And yours is every eye.

Gray blossoms in the road again,

Gray petals in the sky.

This version of Spring Passing shifts back and forth between metered and temporal notation, allowing the violin and marimba to float in and out of phase with one another, like two closely connected spirits in different states of being.

In 2001, Dillon completed an opera about a small American opera company producing an eighteenth-century opera. The main character is a brilliant but unstable soprano. Halfway through Act I, she sings an aria in which she attempts to describe her relationship with her instrument, in a credo for all artists:

The Voice,

The Voice in me,

has a life of its own.

It hovers in my heart,

It shivers in my bones.

A will of its own, within me.

A turning, trembling tone,

tearing me in two,

piercing my vision,

decision,

my choice.

A soul of its own

within mine.

And when it’s gone,

When it’s done with me,

I am here,

I am alone,

a moist and momentary home for

The Voice.

The final piece on this disk, The Voice is a transcription and embellishment of that aria for violin and piano.

– Jeffrey James